It’s no secret that salmon need all the help they can get!

The Mendocino Land Trust is proud to release this update on our Chamberlain Creek Fish Passage Project, which has been years in the making. Almost $1.5 million will be required to assess, design, and execute this project to help remove barriers to salmon migration. MLT secured grant funding from the CA Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Fisheries Restoration Grant Program to design a new creek crossing that will replace an existing culvert currently blocking passage for juvenile salmon!

Below you can read an abridged version of the assessment of the problematic culvert on Chamberlain Creek. Kudos to those on our grant-writing and stewardship team who have worked hard to help restore access for coho salmon and other aquatic organisms.

Project Design Memorandum

Passage Design Project (Abridged & Edited by MLT)

The objectives of this project (by the Pacific Watershed Associates) were to develop a design to improve passage for coho salmon and Pacific lamprey at a single crossing. This crossing is a barrier for coho adults and juveniles in Chamberlain Creek, a tributary to the North Fork Big River.

Chamberlain Creek supports endangered coho population.

This identified culvert is limiting access to about 1.6 miles of upstream habitat, and it is at a high risk of failure.

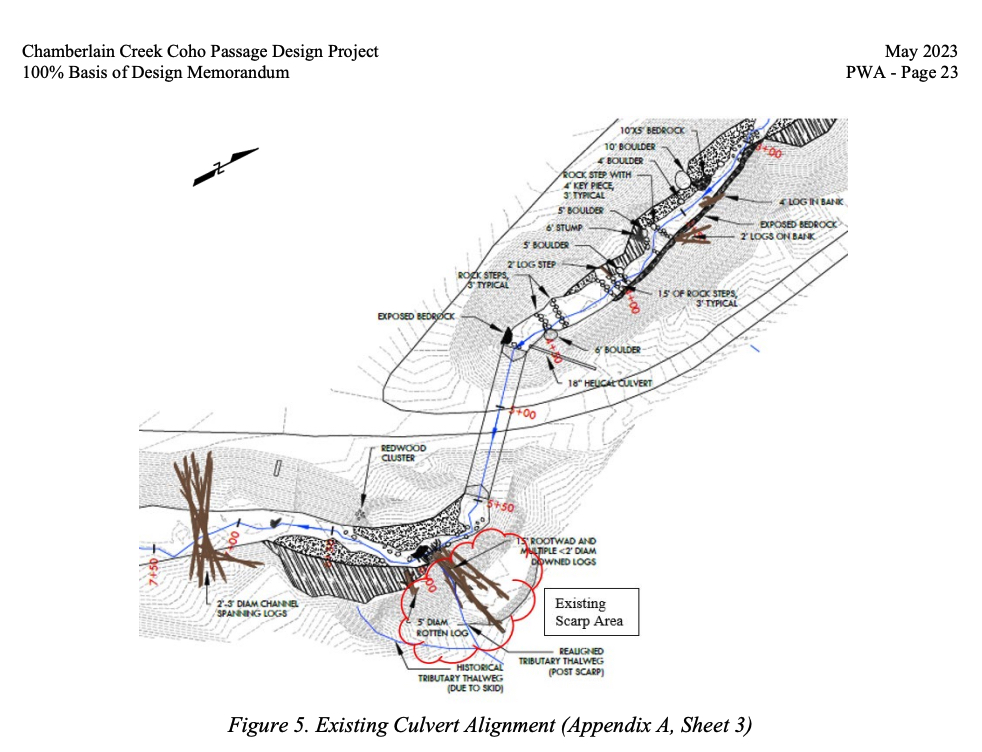

The existing fish habitat was evaluated under low-flow conditions beginning 300 feet downstream from the culverted crossing and ending 300 feet upstream from this crossing.

The crossing was described in a 2011 Stream Inventory Report as having a 0.7-foot plunge at the outlet with some holes in the culvert bottom, and coho juveniles were observed above the crossing. However, in a 2021 survey, by Pacific Watershed Associates, no coho juveniles were observed above the crossing. PWA’s survey also found that the culvert’s condition had degraded over 10 years and nearly all the stream flow was through the rusted bottom and under the culvert.

This Passage Design Project 100% Basis of Design Memorandum details the culvert’s current condition, fish passage potential for coho salmon, and plans for removing and replacing the culvert.

The culvert is failing, and the bottom is nearly rusted through and the creek flows underneath. Sediment accumulation limits pool-jump depths required for adults to leap into the culvert and travel upstream. Deeper water levels within the culvert could also present as a barrier for adults, where the laminar flow velocities could exceed the burst speed needed for an adult to each the upstream side.

Although inaccessible under current conditions, and most likely under flows during winter and storm events, the habitat above the Chamberlain Creek culvert is suitable for spawning and rearing coho and other salmonid populations, and for Pacific lamprey populations, which all depend on this tributary watershed.

This article is an edited portion of a 112-page report prepared by: Pacific Watershed Associates Inc. That document, which can be viewed here, includes PWA’s design plans.