What is Conservation?

What is Conservation is another in our occasional series on issues in conservation, Conservation Explained. This time we go back to basics.

Let’s start at the very beginning. Here is our mission: The Mendocino Land Trust conserves and restores habitat, scenic areas and working lands while also providing public access to beautiful places.

What exactly does it mean to conserve something?

Merriam-Webster says conservation is “a careful preservation and protection of something; especially: planned management of a natural resource to prevent exploitation, destruction, or neglect.”

Many things can be conserved – think back to your physics education and you may remember the conservation of matter. And anyone who’s careful with money or plastic or quilt scraps is conserving resources, too. We at MLT conserve land.

The dictionary definition tracks pretty closely with what we, and other land trusts, do. We carefully – deliberately – protect the land we steward to prevent exploitation, destruction or, where appropriate, neglect. (Sometimes, neglect is good for restoration, but it’s still a carefully considered decision.)

How is land conserved?

Land trusts all over the U.S. are tasked with conserving land, most often in agreement with private landowners. Governments conserve big tracts – think state and national parks – while land trusts generally conserve smaller parcels. There are three primary ways we protect that land: conservation easements, fee-ownership and transferring parcels to other stewards.

A conservation easement is an agreement between a landowner and a land trust to limit development on a particular piece of land in perpetuity. (For more on this, check out our discussion here.) Fee-ownership is just another way of saying that we take ownership of the land; Seaside Beach and Pelican Bluffs are preserves MLT owns. Lastly, occasionally we work with several landowners or agencies to conserve a piece of land and then dispose of it to another entity to look after; for example, the Caspar Uplands was acquired by MLT in 2000 but now belongs to California State Parks. And, yes, if you’re wondering, “dispose” is the technical term for “transfer.”

We decide whether land is worth conserving by determining its conservation values and put the most effort into conserving pieces with high conservation value. Determining whether something has conservation value is complex, but it usually includes surveying the land for important or endangered species, vital habitat, whether it is contiguous with other conserved lands, and even what public access is available. Increasingly, land trusts are attempting to estimate the carbon reserves of a given parcel, though this is difficult to measure. Still, fighting climate change is one reason land trusts do what they do, and this is an exciting avenue for our growth. Also, land trusts increasingly consider the cultural and social values of a piece of land, especially to tribal communities nearby.

The Mendocino Land Trust Receives a $250,000 Grant from the Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation Program

On Thursday, December 15, 2022, the California Strategic Growth Council (SGC) approved over $74 million in grants to protect 54,000 acres of agricultural lands at risk of development. They also awarded 20 capacity building grants and three planning grants. The investments are part of Round 8 of the Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation Program (SALC), a state program that protects agricultural lands, reduces greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and strengthens rural economies.

The Mendocino Land Trust (MLT) is the fortunate recipient of a $250,000 capacity building grant. This grant will help facilitate the development of agricultural conservation acquisition projects in Mendocino County. It will enable MLT to redouble their outreach efforts to local ranchers and farmers who seek to conserve their working lands. Conservation easements and direct purchase of agricultural lands will accelerate progress towards California’s Natural and Working Lands goal to conserve 30 percent of California’s lands and coastal waters by 2030.

The Strategic Growth Council’s SALC Program is a component of SGC’s Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities Program (AHSC). SALC complements investments made in urban areas with the purchase of agricultural conservation easements, development of agricultural land strategy plans, and other mechanisms that result in GHG reductions and a more resilient agricultural sector.

The program invests in agricultural land conservation with revenue from the California Climate Investments (CCI) Fund, made available for projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions while providing additional benefits to California communities. CCI is derived from quarterly cap-and-trade auction proceeds, which are administered by the California Air Resources Board.

As Conrad Kramer, Executive Director of MLT notes, “MLT is tremendously grateful to the SGC and SALC team for supporting and awarding this grant application.The SALC grant is a huge win for the land trust as it will help build MLT’s long-term organizational, structural, and financial capacity to develop agricultural conservation projects. Through improved internal operations and increased staff time, MLT will more effectively seek out and engage with farmers and ranchers interested in conserving their land through voluntary conservation easements and fee acquisition purchases. We look forward to working with local farmers, ranchers, and other stakeholders to support and protect the County’s valuable working lands to ensure a resilient local food system.”

Conservation Easements

The idea of conservation is simple: It is the protection of wild and important land. But exactly how the Mendocino Land Trust makes sure land is protected, habitats are healthy, and the public gains access to beautiful places is complex work. This is the first in an occasional series called Conservation Explained.

This month, let’s focus on Conservation Easements, which are a critical part of our work to expand protected land and habitat in Mendocino County.

What Is a Conservation Easement?

Conservation Easements – or CEs as we call them around the office – are agreements between a landowner and a government or nonprofit entity, like a land trust, to limit development and environmental destruction on all or part of the landowner’s land in perpetuity. CEs are attached to property deeds, so future property owners must abide by the terms of the CE as well. A CE might limit how much building can be done on a parcel, what acres or species must be left untouched, or how the land can be used. The reason an agreement is made between the landowner and a land trust is that the agreement requires a commitment to monitor the land and enforce the terms of the agreement in perpetuity. At MLT, we monitor 26 such easements, totaling more than 14,500 acres, with more CEs in the works.

What are the Benefits and Drawbacks of Conservation Easements?

Conservation Easements allow landowners to protect the property they love, even after the property passes to their heirs or if the property is sold. Monitoring and enforcement provisions provide peace of mind that their cherished place will remain a home for wildlife and that special landscapes will be protected for generations. Most landowners donate conservation easements to land trusts, which means they are giving the land’s development potential to the land trust. However, tax deductions may make the CE donation financially beneficial for the landowner. On rare occasions a land trust could actually purchase the CE, or the land’s development potential, from the landowner using governmental grants. This is usually only possible if the land exceeds 1,000 acres and is very important ecologically. Land with important agricultural soils can also receive grant funding for CE purchase. These do not need to be large acreages

Unfortunately, creating CEs can be very expensive to process. Between the documentation required and the donation needed to fund ongoing monitoring work, this version of conservation can be expensive for individual landowners. MLT and other land trusts are exploring ways to assist people with these costs, but it remains the biggest barrier to this kind of conservation. Landowners should also be aware that, while the overall financial results may be positive, restricting development in this way could bring the property value down.

Do You Have Property to Conserve?

If you have a piece of land you would like to conserve for future generations, this is one way you can protect it. If you would like to talk to our conservation project managers about whether a CE is right for you, let us know here!

Beaches, Bucket Lists, and Accessibility

“MLT’s monthly Outdoor Social Club has introduced me to new public lands, butterflies, nature journaling, night skies, and most recently a beach wheelchair!”

– Leslie Krongold, Mendocino Resident

Mendocino Resident and frequent MLT Outdoor Social Club participant has written a guest post about beaches, declining mobility, and bucket lists. We hope you enjoy this short read. Make sure to watch the video at the bottom of Leslie taking a beach wheelchair for a test drive at Seaside Beach. Thank you Leslie for sharing your story! Learn more about Leslie and listen to her excellent podcast at glasshalffull.online

Do you have a story to share? Email info@mendocinolandtrust.org to submit it for inclusion on our website.

Leslie writes…

Growing up in South Florida I had the luxury of visiting the beach regularly. I remember my father coming home from work and my parents and I would hit the beach in the latter hours of a summer day. I’d sit on the sand, legs spread out with the water shimmering around me, and daydream. Lots of daydreaming.

I’ve never lived too far from the beach – East or West Coast. But the one thing that I didn’t have, and it was on my very short bucket list, is to wake up and see the ocean. Effortless.

Effort has become a key word for me lately. I have a rare genetic neuromuscular disease called myotonic dystrophy. It’s progressive and since my diagnosis I’ve made adaptations based on my new normal. It takes an effort to eat, to breathe, and now to walk.

During COVID, while living in Alameda, we naturally didn’t travel. We’d take a daily walk around the neighborhood. Our love of nature intensified. When we knew it was okay to be outdoors around people, we made a trip to Ocean Beach in San Francisco.

Access to the beach was difficult, and I couldn’t handle the steps leading from the pavement down to the sand. We eventually found a concrete ramp. I slowly made it to the shore and reveled in the intoxicating sights and sounds. We realized my mobility was declining and either we do a massive remodel of our 1920s Tudor home or move to a modern house with an open layout.

Considering my bucket list, we decided to move to the Mendocino Coast. I now wake up and see a bit of the ocean landscape. Shortly after we moved, I had an unfortunate fall and recognized it was no longer safe for me to walk outside. I now use a walker or power wheelchair. They’re great but they can’t handle a sandy beach.

I’ve been on a crusade to identify all accessible nature trails. And that’s how I discovered the Mendocino Land Trust. Their monthly Outdoor Social Club has introduced me to new public lands, butterflies, nature journaling, night skies, and most recently a beach wheelchair! I’m forever grateful to MLT Outreach Coordinator Amy Wolitzer for making that effort to borrow a beach wheelchair so I could fully participate in the August event at Seaside Beach.

Photos from our MLT Outdoor Social Club event at Seaside Beach. MLT Outdoor Social Club events are free and open to all who would like to participate. These events allow the community to celebrate what conservation has accomplished locally and giving people a chance to connect to the land in a variety of ways. Questions about accessibility? Have an idea for an event? Let’s talk! Send an email to info@mendocinolandtrust.org or give our office a call at (707) 962 0470

Check out the MLT events page for upcoming events.

Borrowing a beach wheelchair

A beach wheelchair, free of charge, is available upon request for use at California State Park beaches in the Mendocino coast area. Call (707) 937-5721 at least 7 days in advance to reserve the beach wheelchair. Please note the wheelchair does not fold up and you will need a truck or SUV to transport the wheelchair from the kiosk or Visitor Center to the beach. (State Parks may be able to deliver the chair to a parking area upon request.)

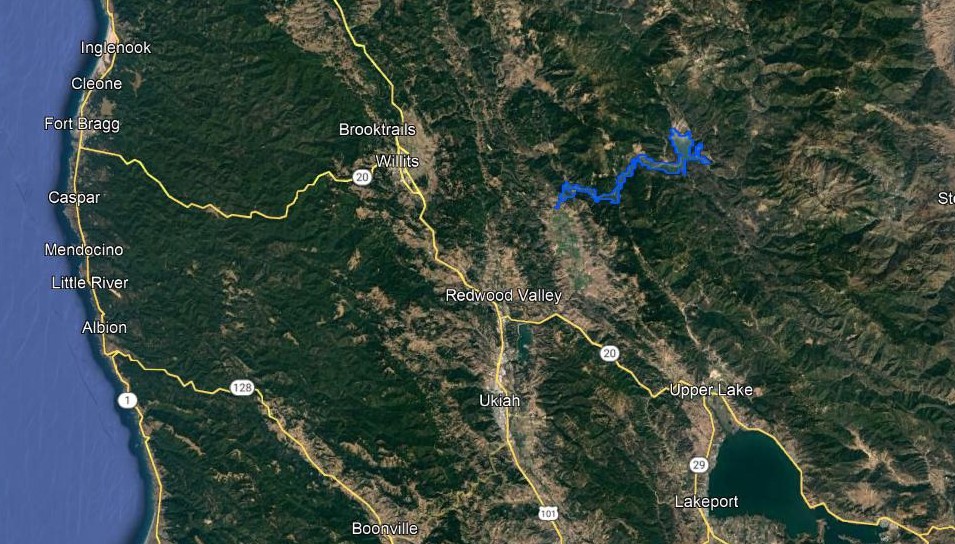

Lake Pillsbury and Eel River lands are now protected!

“One of the exciting aspects of this conservation easement is that it protects public access too. Most conservation easements protect habitat on privately owned land. This is the case here, too, but protecting public access to Lake Pillsbury and the Eel River is also an important part of this conservation easement.”

– Conrad Kramer, Mendocino Land Trust Executive Director

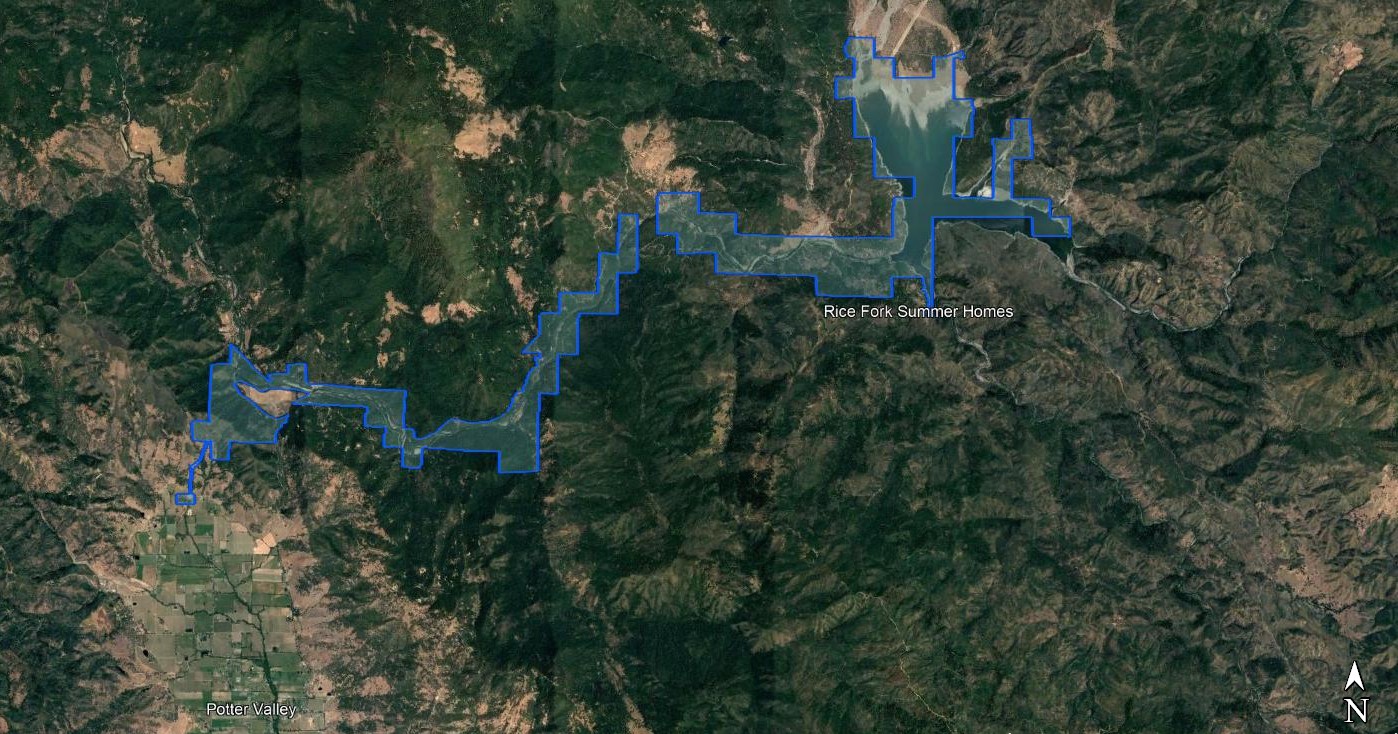

This month, thanks to our supporters, the Mendocino Land Trust completed its LARGEST conservation easement to date! 5,620 acres in the Eel River watershed, including the land around Lake Pillsbury, will now be forever protected from further development and habitat degradation. With the addition of these lands, the total acreage MLT has helped protect since 1976 is nearly 25,000 acres.

While the land protected by this conservation easement continues to be privately owned, MLT is now able to ensure perpetual protection of this rich wildlife area that is home to a great diversity of species. The river supports Chinook salmon and steelhead. Bald eagles and osprey are frequently seen around Lake Pillsbury – as well as a magnificent herd of wild tule elk at the northern end of the lake.

The Eel River area is a hugely important watershed in Northern California. “This conservation easement covers the mainstem of the wild and scenic Eel River,” explains Nicolet Houtz, MLT’s Director of Stewardship. “This area is particularly important because it is largely undeveloped and adjacent to National Forest and US Forest Service lands. This ensures permanent protection of a connector of these lands.”

Conrad Kramer, Mendocino Land Trust’s Executive Director says, “One of the exciting aspects of this conservation easement is that it protects public access too. Most conservation easements protect habitat on privately owned land. This is the case here, too, but protecting public access to Lake Pillsbury and the Eel River is also an important part of this conservation easement.” Lake Pillsbury is a popular recreation destination accessed through Potter Valley in eastern Mendocino County. There are campgrounds within the conservation easement including the lovely Trout Creek campground along the Eel River.

The conservation easement will prevent these large contiguous parcels from being divided into small parcels and sold. If this were to happen it might open the door to a multitude of development and construction projects in a very wild area. The building of roads to access these parcels would have detrimental effects on the landscape and river health, and construction of homes and structures would introduce pollution sources and all the unfortunate consequences that come along with human habitation. Annual monitoring of the conservation easement by MLT staff will make certain that present and future landowners honor the commitments made to protect this important property.

The two large parcels now protected by a conservation easement are owned by PG&E. As part of its 2003 bankruptcy settlement, PG&E was required to ensure conservation of all of its “nonessential lands”. This larger project to conserve PG&E lands was overseen by the Pacific Forest and Watershed Lands Stewardship Council.The Stewardship Council is a private, nonprofit foundation that is responsible for developing and implementing a land conservation plan for approximately 140,000 acres of PG&E-owned watershed lands. It requires that the lands be preserved and enhanced for:

• protection of the natural habitat of fish, wildlife, and plants

• sustainable forestry including fuel and fire management

• outdoor recreation by the general public

• preservation of open space

• historic and cultural values

This conservation easement has been in the works for a long time. Mendocino Land Trust staff and others have spent many hours documenting baseline conditions and natural resources within the easement area. Houtz has enjoyed her time here, participating in many surveys over the past decade. She says one of her favorite things about the area is that “the Eel River canyon is steep and still mostly wild and natural.”

On Aug. 16, 2021 the California Public Utilities Commission approved the designation of PG&E’s approximately 5,620 acre Eel River property with a Conservation Easement held by Mendocino Land Trust. The conservation easement closed on June 24 – Houtz’s birthday! She had extra cause to celebrate this year – as do we all with the protection of these lands.

How I Acquired a Forest

This inspiring essay and photos were submitted by a Land Trust supporter who asked to be identified as “RA.”

I wince every time I see redwood forests cut down when I know their natural life cycle should reach more than 2,000 years. The giant, ancient trees growing in Mendocino County in the 1800s are largely gone, replaced by second and third-growth younger forests. What if we allowed more of those trees to grow back to their full potential?

When a real estate agent recently mentioned that a second-growth redwood forest of about 40 acres was coming on the market in the southern part of the county, I knew I had to go see it. The listing included a proposal put together by a forester that laid out the financial benefits of logging it. One could cut down the trees and earn a ridiculous amount of money. I sensed trouble ahead for this forest.

My spouse and I drove down a dirt road to view the property, dropping into a shady canyon with a seasonal creek surrounded by redwoods. We parked and explored. Sword ferns lined the streambed, and every square foot of earth where sunlight landed had something green growing on it: huckleberry bushes, rhododendrons, salal, mosses. We startled a deer, watched a banana slug inching along and listened for birds. A curious raven circled overhead keeping an eye on the humans below.

In the transition zone above the creek, alder trees were just dropping some leaves for the autumn. Giant redwood stumps dotted the forest from previous timber harvests more than a hundred years ago. The upper part of the property had a different group of trees: conifers such as bishop pine, grand fir, and Douglas fir. In spite of a very dry summer, everything looked green and moist due to the fog wafting up from the coast.

I came home with a mission to find a conservation buyer so that piece of forest could stay intact. Two weeks of contacting potential buyers led me to sympathetic forest-lovers but no one willing to purchase it. One day, the real estate agent called me and said an offer from a timber buyer had just come in, and they wanted a response within two days. The urgency increased.

Enter Mendocino Land Trust (MLT), which put me in touch with a woman who was a private conservation landowner. We had a long conversation, and she inspired me to be the conservation buyer myself. Gulp. Do I need a forest? Not really. Do I want to protect it? Absolutely.

Negotiations with the seller, who favored a buyer who would leave the trees standing, led to an arrangement where she offered to lend part of the purchase price on favorable terms. MLT offered to help with a conservation easement to protect the forest. Things were coming together. I submitted an offer, waited a nail-biting couple of days and finally received the call: “You got it!”

Now the work begins to clear two decaying structures from the property and familiarize myself with the unique features of this place. What lives here and how is it all related? As I explore and learn the names of the various species which call this place “home,” I develop a new respect for the plants, animals, fungi and trees that dwell here, finding the resources they need to thrive.

Do I own a forest … or do I now belong to this community of living non-human beings? I’m beginning to understand the Native American concept of reciprocity. Forests provide for us in a multitude of ways, and now it’s our turn to protect and steward them into the next century and beyond. Thank you to Mendocino Land Trust for timely assistance!

RA

The Mendocino Land Trust is thrilled to begin work with this new landowner, who has requested not to be named, to ensure that the forest she stepped forward to save is protected forever. We hope RA’s story will inspire others to take action when they see a natural area in peril.

Learn more about conservation easements here.

Do you have a conservation story to share? Email us at info@mendocinolandtrust.org

The Truth About Black Bears

Bear with us for a moment. It’s time to put away your picnic basket and talk about the American black bear (Ursus americanus).

North America’s smallest bear, the American black bear is also California’s only living bear species. They inhabit forested areas all over the North Coast, moseying through the forest foraging a diet of mainly plants (and only sometimes honey). Roots, berries, and the occasional fish make up the bulk of their diet.

Black bears can come in a variety of different coats, from black to brown to nearly blonde. How can you tell if you’ve rediscovered the fabled California grizzly or have just seen a big brown black bear? The easiest ways to tell them apart include a much smaller shoulder hump in black bears and a rounder face, as grizzlies often have sharper angles from skull to snout.

Ursus americanus doesn’t always hibernate, depending on how much food is available, but when they do it can be for up to six months! During this time they do not eat, drink, or go to the bathroom, and they can lose up to one-third of their body weight. The bear’s life cycle is based around this time period, as mating occurs in the summer but embryo development is paused until the expectant mothers are tucked away in their winter dens. Once born, the cubs will nurse and stick with mom for up to 18 months learning the “bear necessities” of life before venturing out on their own.

According to the Be Bear Aware Campaign, black bears number about 600,000 in North America, and they are amazingly dexterous and intelligent. This can lead to conflicts with humans. Bears have been known to open car doors and unscrew the lids off jars, leaving a trail of destroyed upholstery and sticky messes along the way.

But don’t be afraid to venture into the woods just because bears are out there. When walking through the forest a simple shout of “hey bear!” is usually enough to send one running from you before you even see it. See this clip. According to the North American Bear Center, in the last 124 years, there have been 61 bear-related human fatalities in North America, far fewer than the average of 27 annual lightning-strike deaths in the U.S. cited by the Encyclopedia Britannica!

The U.S. National Park Service offers this advice if you come across a bear:

Consider yourself lucky, but remember these simple rules:

- Stay together, especially with small children.

- If a bear changes its behavior because of your presence, you are too close.

- Don’t get between a female and her cubs.

- Don’t linger too long.

So, you should be alert when in bear country. Non-fatal “interactions” do happen. The California Department of Fish and Game has a listing of 99 bear incidents from 1986-2015. The incidents range from zero in 1987, 1988, 1999, to a high of six in 2015. None of the 99 reported encounters were fatal. But having a bear center-punch your car’s rear window can ruin an outing!

The best way to guard against an unplanned and unpleasant bear interaction is to lock up any food in bear canisters and never keep food, trash, or even toiletries in your tent when you’re in bear country. Here’s a list of problematic items from the Park Service.

- garbage and recyclables

- soap, shampoo, toothpaste, sunscreen, first-aid kits, baby wipes, lotion, hairspray

- scented tissue, air fresheners, candles, insect repellent, cleaning products

- pet food, tobacco products, baby car-seats

- any food item, including dry goods

- any beverages, whether they are opened or closed

And for the record, Yogi-the-Bear and Boo Boo were … gasp … BRUINS! (AKA Grizzlies). But no need to worry. That pair never ventured outside of Jellystone Park. So, while hiking in Mendocino County, your lunch-time treats are safe….

Mostly (see above).

It’s Earth Day – A Great Time To Step Up!

“We do not inherit the Earth, we borrow it from our children.” Chief Seattle

Dear Fellow Conservationist,

We know you care, and that’s why we’re reaching out today, Earth Day, and encouraging you to step up again and be a part of MLT’s ongoing work. Alas, protecting the planet is not a once-and-done job. It falls to all of us to be the Earth’s guardians. Forward-thinking people have long known this to be a special obligation, literally a trust.

That’s why we are asking you to join forces with us and empower MLT to conserve more land, protect more wildlife, restore more habitats, and create more public access.

How? By making a monthly donation. Why monthly? There are several reasons.

First, it smooths out your donations into smaller, manageable bite-size contributions. And—this is the best part–at the same time, it helps us a great deal. Monthly donations allow us to plan better, to commit to projects knowing we have the resources, and to, frankly, keep the lights on even during lean times. Grants and big-donations may make the news, but your regular, recurring, donation really keeps us going! In fact, to encourage you to make the switch to monthly support of at least $10 a month, we’ll throw in a thank-you gift—a cool MLT T-shirt!

And it’s easy!

Check out the link below and within minutes you’re set and making a difference. Really! MLT has a long and proud history, thanks to people like you. But we’re not resting on past accomplishments. Look at the images below to see what is currently in the works. Help us continue to do the sort of work that can only be done by caring conservationists.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed individuals can change the world. In fact, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

Margert Mead

Thank you again for all your previous support. We are accredited and careful stewards of your trust, and have earned “Candid” rating from the Gold Transparency 2024 and a four-star (top) rating by the Charity Navigator, and we have many testimonials that speak to our passion and hard work.

“Soon after purchasing a second home in Fort Bragg, we became acquainted with the Mendocino Land Trust. From land restoration and cleanups to trail-building and habitat protection, MLT has built a solid legacy of preservation. While reading through a newsletter last year, we were impressed with the organization’s scope and realized it was time to ‘up the ante.’ Thank you MLT and the MLT volunteers, for making Mendocino County a better place to live and visit!”

Holly/Chuck, Lake County/Fort Bragg

Please take a moment to visit this link and help change the world!

Flashback Friday – Earth Day 1971

Earth Day as covered by the Independent Coast Observer in April 1971. Used with permission. All rights retained by the ICO.

Western Toads – Don’t Let Them Croak

The western toad (Anaxyrus boreas) is one of California’s most common toads. They may look mean with their warty appearance, but, please, don’t give them the boot!

These docile forest creatures are perfectly content with a life of hibernation and snacking. And the other critters in their habitat know to leave them alone. Western toads contain a mild toxin called bufotoxin that is produced in their skin. This isn’t especially dangerous to humans, but it can prove deadly to the suite of predators in the forest looking for a quick meal. This toxin is also present in their eggs for the same reason, assuring the masses of tadpoles you can see in ponds each spring.

Breeding is triggered by winter rains. These rains initiate a mini-migration of sorts, when the toads venture from their moist forest homes and congregate in wetlands to find mates. This process begins in lower elevations as early as January, but in the mountains and in areas with cooler temperatures, breeding may not occur until March. Males make a high-pitched chirrup or chattering to attract females. You can hear a sample by clicking here.

Once they have mated, females will lay thousands of eggs in standing water. Peak egg laying usually happens in April. The eggs develop and hatch in about a week. From there, the inch-long tadpoles live an aquatic life feeding in the natal pools until late summer when they metamorphose into adults. This process has them grow legs, reabsorb their tails, and develop lungs to replace their gills. This allows them to adapt to a terrestrial lifestyle. Once metamorphosis is completed, western toads will hop along to find a moist burrow to wait for the winter rains again.

In recent decades, western toad populations have been hit hard by a disease called chytridiomycosis. This disease is caused by several chytrid fungi species that began spreading around the globe in the 1970s and 1980s and has caused extinctions in some amphibian species. The fungus enters the skin of the toads and can lead to a range of effects from sloughing of skin to bizarre behavioral issues, eventually resulting in death. While the western toad hasn’t been hit as hard as other amphibian species, climate change creates more suitable areas for the fungi to colonize and potentially wreak havoc on populations.

What can you do to help?

You can avoid contaminating their habitat with soil from elsewhere. Cleaning your footwear between hikes, especially in wet areas, can help limit exposure and may promote many more mini-migrations in the future!

So, be boot aware! The toads will thank you… by not croaking.

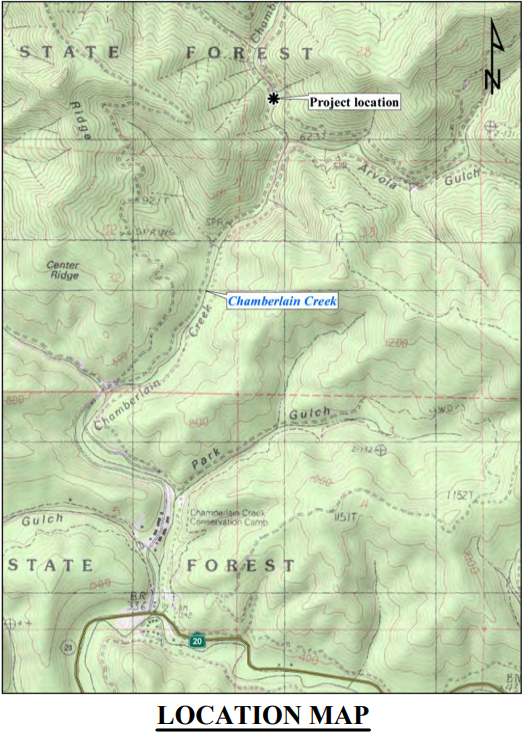

Chamberlain Creek Project

It’s no secret that salmon need all the help they can get!

The Mendocino Land Trust is proud to release this update on our Chamberlain Creek Fish Passage Project, which has been years in the making. Almost $1.5 million will be required to assess, design, and execute this project to help remove barriers to salmon migration. MLT secured grant funding from the CA Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Fisheries Restoration Grant Program to design a new creek crossing that will replace an existing culvert currently blocking passage for juvenile salmon!

Below you can read an abridged version of the assessment of the problematic culvert on Chamberlain Creek. Kudos to those on our grant-writing and stewardship team who have worked hard to help restore access for coho salmon and other aquatic organisms.

Project Design Memorandum

Passage Design Project (Abridged & Edited by MLT)

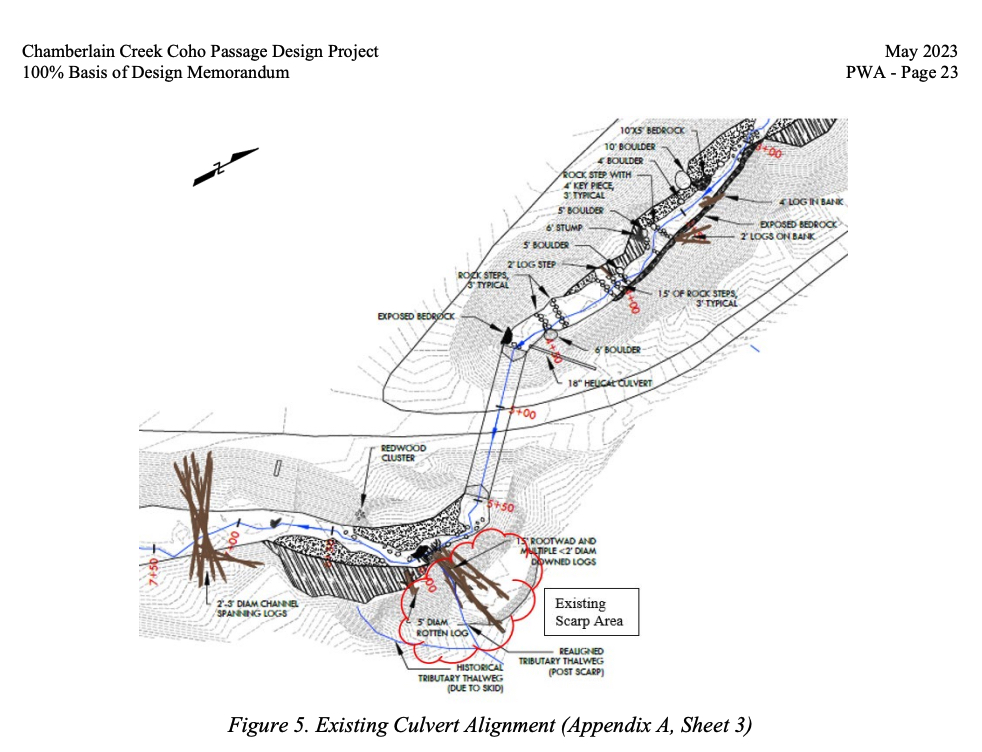

The objectives of this project (by the Pacific Watershed Associates) were to develop a design to improve passage for coho salmon and Pacific lamprey at a single crossing. This crossing is a barrier for coho adults and juveniles in Chamberlain Creek, a tributary to the North Fork Big River.

Chamberlain Creek supports endangered coho population.

This identified culvert is limiting access to about 1.6 miles of upstream habitat, and it is at a high risk of failure.

The existing fish habitat was evaluated under low-flow conditions beginning 300 feet downstream from the culverted crossing and ending 300 feet upstream from this crossing.

The crossing was described in a 2011 Stream Inventory Report as having a 0.7-foot plunge at the outlet with some holes in the culvert bottom, and coho juveniles were observed above the crossing. However, in a 2021 survey, by Pacific Watershed Associates, no coho juveniles were observed above the crossing. PWA’s survey also found that the culvert’s condition had degraded over 10 years and nearly all the stream flow was through the rusted bottom and under the culvert.

This Passage Design Project 100% Basis of Design Memorandum details the culvert’s current condition, fish passage potential for coho salmon, and plans for removing and replacing the culvert.

The culvert is failing, and the bottom is nearly rusted through and the creek flows underneath. Sediment accumulation limits pool-jump depths required for adults to leap into the culvert and travel upstream. Deeper water levels within the culvert could also present as a barrier for adults, where the laminar flow velocities could exceed the burst speed needed for an adult to each the upstream side.

Although inaccessible under current conditions, and most likely under flows during winter and storm events, the habitat above the Chamberlain Creek culvert is suitable for spawning and rearing coho and other salmonid populations, and for Pacific lamprey populations, which all depend on this tributary watershed.

This article is an edited portion of a 112-page report prepared by: Pacific Watershed Associates Inc. That document, which can be viewed here, includes PWA’s design plans.

Flashback Friday – April 1976 Ships Return To Noyo Harbor

Flashback Friday – Ships returning to Noyo Harbor, April 1976.

https://www.mendocinobeacon.com/

#flashbackfridays#mendocino#MLT#mendocinolandtrust#noyoharbor

Courtesy Mendocino Coast Beacon, used with permission.

Don’t Mess With Newt!

Don’t mess with Newt!

Say hello to the California newt (Taricha torosa), a local celebrity. You may have seen them bumbling along the forest floor during the rainy season. These newts range from San Diego up to Mendocino County.

With their clumsy gait and cute, doleful eyes, you would think they are just another harmless and quirky addition to California’s fauna. But watch out! They are actually one of the deadliest animals in the world. California newts contain high amounts of tetrodotoxin throughout their bodies.

Tetrodotoxin is an incredibly potent neurotoxin that can kill an adult human if even a fraction of an ounce is ingested. According to reptile scientist Dr. Gary Bucciarelli of the University of California Davis, “Taricha newts should not be handled unless by knowledgeable personnel, because they can contain up to 54 milligrams of tetrodotoxin per individual. Doses up to 42 micrograms per kilo of body weight can lead to hospitalization or death.” Bucciarelli made the remarks in a November, 2023 article in www.phys.org.

In 1979, a 29-year-old man died after taking a bet and swallowing a California newt. But most websites report that you won’t fall gravely ill from quickly moving a newt out of the way and then immediately washing your hands. Still, it’s best to err on the side of caution and avoid contact or carry your handy-dandy disposable plastic gloves!

Why would cute-newt resort to so much overkill? It’s because one of their few predators — the California garter snake – is resistant to tetrodotoxin. This is an example of how nature stages an arms race, where predators and prey species evolve specific adaptations over time in response to one another. In this case, the newts have evolved to be unbelievably toxic while the garter snakes have evolved to find them unbelievably delicious.

Now you may think: “Well … how does being more deadly than cyanide help when you’re already being eaten?” And that’s a fair point because it actually doesn’t. What it does do is take down the predator with you, assuring your remaining newt friends and family won’t meet a similar fate at the hands of that particular snake or peckish raccoon.

And this does not mean that the newts go impassively and quietly into the night. Their main defense warning is to arch back their heads and tails in a sort of silly yoga pose, exposing their bright orange underbelly. This is the newt’s color-coded roadway-hazard warning to potential predators. Things that are bright and visible in nature are usually colorful for a reason. In this case it’s not about mating, it’s about toxicity.

These newts have also been known to flip on their back with the drama of a Shakespearean actor to convey that same message. Quite a curtain call when your back is against the wall.

When they aren’t polishing off anything foolish enough to lay their lips on them, the California newt is either eating, mating or hibernating until the next rainy season. A classic springtime scene in forest puddles is a “newt ball,” a cartoonishly large dogpile of male newts all wrestling for the chance to mate with the female who is usually at the center. So, they do romantic comedy, too!

Newts can be very active on rainy evenings. Please be careful to avoid them if they’re crossing roads!

And don’t eat them.

Flashback Friday – Heider Field & The Origin Of MLT

The earliest days of land conservancy in Mendocino county began with local citizen’s desire to preserve open space in Mendocino. This article, from the February 26, 1976 edition of the Mendocino Coast Beacon documents one of the first steps towards what ultimately would be the first project of the group behind the formation of the Mendocino Land Trust. Article courtesy The Mendocino Beacon, used with permission.

Fun Fact – 4/6 Is Poppy Day!

The California poppy (Eschscholzia californica) is out in force, and–get this–it has its own official holiday!

I guess that means it gets the day off?

It’s true. April 6th of each year California celebrates this visual reminder of our Gold Rush days. The poppy was named our official state flower in 1903. Contrary to popular belief, it is not illegal to pick–on your own land–but grabbing one off a roadside may well violate trespassing and petty theft laws. Besides, poppies last so much longer in the ground, are there for everyone to enjoy, and stand a better chance of being there again next year in even greater numbers.

Check out these links for more information on California’s native plants, and plants you should NOT plant in your yard or garden.